How a self-taught outsider became Japan’s financial savior—and predicted Keynes before Keynes.

Before he led Japan through the Great Depression, Takahashi Korekiyo was a penniless servant, a failed entrepreneur, and a doorman at the Bank of Japan. He had no formal education, no elite pedigree, and no patience for convention. Yet through wit, resilience, and sharp economic instinct, he became one of the most influential financial minds of the 20th century. This is the improbable story of the man history now calls “the Japanese Keynes.”

Takahashi Korekiyo was born into hardship—as the illegitimate son of an elderly artist and a 16-year-old maid. He was adopted by a low-ranking samurai, significantly beneath his biological father’s social standing. At age ten, he was sent by the local governor of Sendai to the newly opened port of Yokohama to learn English. There, he entered the household of Alexander Allan Shand, a Scottish banker who would later become a financial advisor to the Japanese government.

At thirteen, Takahashi boarded a ship to San Francisco with a friend and several hundred Chinese laborers. Once again, he found himself in domestic servitude—this time under far harsher conditions. In the racially stratified, slave-tolerant America of the mid-19th century, he was made to eat with the household dogs and forbidden from using a kerosene lamp to read at night. Historians still puzzle over when or how he learned to read and write Japanese; he left Japan so young that his literacy seems almost miraculous.

After arriving in the U.S., he briefly worked for Van Reed, a man infamous for his brutality toward Hawaiian plantation laborers. Takahashi’s appetite for books and independent thinking made him “difficult,” and he was soon dismissed. He ended up in Oakland, where he discovered—through a conflict with a plantation overseer—that he, like many others, was essentially enslaved.

He was eventually rescued by older Japanese immigrants who had come from New York and helped him return home. By then, he spoke fluent English and had come to realize that, in the eyes of many Westerners, Japanese and Chinese people were indistinguishable. It was a lesson that would serve him well—if bitterly—years later during financial negotiations in London.

Back in Japan, Takahashi’s linguistic skills and international experience quickly proved invaluable. His career ascended rapidly through several government ministries, where he met Maeda Masana, a statesman he came to revere. From Maeda, he learned the importance of integrating agriculture with craft industries, and also internalized a vision of the state that remained with him for life: the state is not an abstract or ethereal entity, but a living structure made up of individuals—just like a nation or an identity.

Though he had no formal education and only a few years of bureaucratic experience, Takahashi’s intellect and drive astonished his older colleagues. His flamboyance was legendary: he would sometimes arrive at work with an older geisha, and he wasn’t above ordering sake to make office life more pleasant. He embraced life with full enthusiasm, whether in policy work or nights spent in pleasure quarters—and he had no patience for disapproving elders.

Eventually, Takahashi grew weary of government work and left for Peru in pursuit of private fortune. He invested all his savings in a business venture—and lost everything. With barely enough money for a return voyage, he went home broke but wiser.

Seeking a fresh start, he turned to the newly established Bank of Japan. The only job available? Doorman. Undeterred, he took it. It was the beginning of one of the most remarkable financial careers in Japanese history.

He soon rose through the ranks, working alongside finance minister Matsukata Masayoshi to stabilize Japan’s budget. He led a Yokohama-based bank specializing in foreign exchange and helped establish the yen’s gold standard—using funds paid by China as reparations following Japan’s victory in the First Sino-Japanese War.

One colleague later remarked that Takahashi always rose to leadership in times of crisis—first as a minister, then as central bank governor, and finally as a statesman. His most significant contribution came during the Great Depression. Between 1929 and 1933, he steered Japan out of financial turmoil by devaluing the yen and expanding government spending. His strategies anticipated, by three years, the core recommendations of John Maynard Keynes. For this, he would later be dubbed the “Japanese Keynes.”

Takahashi himself explained his economic philosophy with a disarming simplicity. In a well-known analogy, he argued that during hard times, people often frown on a man spending money on a geisha. But that money allows her to buy food, clothing, and cosmetics—supporting tailors, grocers, and merchants. The more people spend, he reasoned, the faster the economy recovers. The state, he insisted, should do the same.

He was also the first Japanese leader to introduce state-sponsored relief for indebted farmers—realizing a decades-old idea proposed by his mentor Maeda Masana.

In 1936, in a landmark parliamentary speech, Takahashi took a stand against rising military spending. He warned lawmakers—and the Japanese public listening on the radio—that war against the United States would spell national catastrophe. He was right, but he would not live to see it.

Later that year, Takahashi was assassinated in his bedroom by a group of radical young officers during a coup attempt. He was 82.

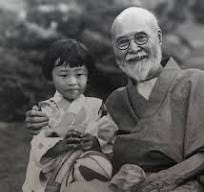

Takahashi Korekiyo—a self-taught financial genius, reluctant bureaucrat, and passionate humanist—left behind a legacy of intellectual courage and practical wisdom. A single photograph remains from the final year of his life, showing him with one of his grandchildren. It was downloaded from the internet on April 25, 2017.